Editor’s Note

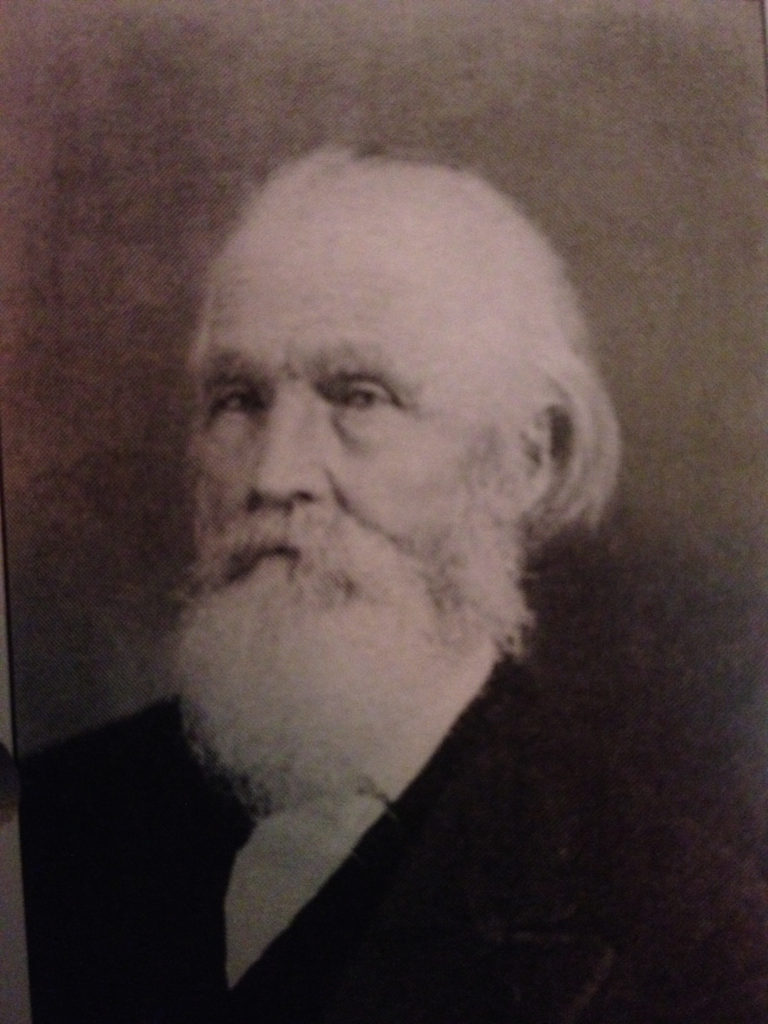

James Monroe (“Roe”) Reisinger’s family came to the French Creek area from Lancaster via Beaver County. Descended from Hessian immigrants who arrived about 1750, the family settled in the 1840s along French and Sandy Creeks. Peter, Roe’s grandfather, was both a blacksmith and a whitesmith. The boys were encouraged to pursue advanced education and Peter’s son Charles moved to Meadville so that his children could attend the Academy. Three of the boys attended Allegheny College.

At the outbreak of the War of the Rebellion, James Monroe “Roe” enlisted in the 150th Regiment, Company H, and at Gettysburg was severely wounded while serving under color-Sergeant Samuel Peiffer. Following his nearly year-long hospital stay (until a bullet could be extracted from his knee), he was assigned to Company B of the 14th Reserve Corps and later served as an officer of the 114th US Colored Troops in Texas until 1867. Resigner wasawarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by special act of Congress for his action at the McPherson barn at Gettysburg.

He returned to Meadville, where he studied law and was admitted to the bar. After a number of years as a newspaper publisher, he worked with the Galena-Signal Oil Company in Franklin, until his retirement. He died at the age of 82 in 1925 and is buried in Greendale Cemetery. This story is an accounting of a rifle once owned by his father, which has been passed down through family. It is presently on loan to the Crawford County Historical Society and on display in our collection.

* * *

This rifle was owned by my father, Charles Reisinger, from about 1820 or 1821 ’til his death in August 1882. It was made by Thomas Allison, of Beaver, Pennsylvania, in 1819. The name of the maker and the date are engraved on the palate under the trigger guard. My father obtained the gun under the following circumstances. Allison was a noted gun maker and had a small museum of specimens of fine workmanship of various kinds. The price he got for his work was a minor thought to him; the beauty and perfection of his guns brought him his highest pleasure.

My grandfather, Peter Reisinger, was a blacksmith and also a whitesmith and was a highly skilled mechanic (the trade of whitesmith was the making of locks, door fastenings, knives and forks, shears and a multitude of other small articles.) He was born at York, Pennsylvania and worked at his trade there for many years. After moving to Beaver County (in 1804) he became acquainted with Thomas Allison and taught him to forge gun barrels from solid iron bar. For this service, Allison said he would make a hunting rifle for each of grandfather’s four sons – Daniel, Joseph, Peter and Charles, as they became of age.

This he did, but when father, who was the youngest, came to manhood Allison told him he owed him a gun according to his promise, but he had then become old ad his hand was no longer steady enough to the fine gun work, and that he wished to make a different arrangement for the fulfillment of his agreement.

Allison, sometime before, had made a heavy rifle which was designed especially for target shooting. A large black bear had been taken in Butler County and was put up as a prize for marksmanship at the town of Butler. The famous shots gathered from all the surrounding county. Allison had made this riffle especially for the contest and with it he won the bear. He told father that the price of the gun was (I think) fifty or sixty dollars, while those he made for the other brothers was fifteen or twenty dollars less, and that my father might pay him the difference in price and he would let him have this gun. He made the further provisions that father was never to loan the gun, and to keep it as long as he lived.

On these terms he got it, and he never violated the conditions. It came to me by his will. Sometime before his death he called me to his bed (though not bedfast he was lying down) and said to me “Roe, you have inherited the hunting blood of you father and grandfather and I will give you Old Grey and I know she will never leave your possession”.

The gun having a stalk of made from curly maple was doubtless the cause of its name. Whether christened by Allison or by Father I am not certain, but I think by Allison, for he regarded the gun with real affection, his feelings likely being tinged by the memory of the joint triumph at Butler. We lived from 1844 to 1850 on Sandy Creek in Venango County, Pennsylvania, and at that time a good hunter could frequently kill a deer. I recollect of Father many times saying to Mother, “I guess I’ll take Old Grey and see if I can get a deer.” Though the gun was very heavy and his hunting was done in a very rocky and mountainous region, I never heard him complain of its weight. I never knew a man who had such a passion for hunting as he. His eye would brighten at the mention of game, and when he was relating one of his many hunting stories the children always knew it was best for them to keep quiet.

A few days before his death he repeated a story which I had heard him tell when I was a child. As it shows his skill as a hunter, I will give it, in almost his exact words. “I was one time going over the Sandy hills with Old Grey, looking for a deer. It was in a red brush clearing, where the bushes were very thick. I had on my moccasins and was careful not to make any noise. As I slipped along, watching out closely, I suddenly saw through the red leaves ahead about forty yards, a black spot about as big as a silver dollar. I stopped instantly. It seems to be too black for a leaf. I looked at it carefully and could just see the outline of the deer’s horns. I knew at once that the black spot was the end of the deer’s nose. I quietly cocked and raised Old Grey to my face and calculating the distance from the buck’s nose to his forehead, I fired away and the buck dropped. I loaded again and when up to him. He was hit fair in the forehead, just above the eyes. He was an eight pronged buck and weighed 280 pounds.”

For more than fifty years this gun was carried by him at all times when hunting large game and most of the time even when squirrel hunting. I was his companion on his last deer hunt when he was eighty years old (in the winter of 1878) he determined to go to Baxter’s Mills in Warren County, Pennsylvania, for a hunting trip. The mills were back from the nearest railway station, five or six miles in the mountains. For a number of days we tramped over the hills, Father carrying Old Grey and apparently unmindful of its weight and his great age. The conditions were unfavorable and our hunt was unsuccessful. On our return we trudged over a rough road through the woods to the Allegheny River, a distance of about six. When we reached home Father was in good condition.

To show Father’s love for Old Grey, I will relate a story. When I was about twelve years old Father was hunting in Dick’s woods. He shot a crow and when his gun went off the screw holding the cock in the lock place broke and the cock flew some distance off. As the ground was thickly covered with leaves, a long search failed to find it. Father was troubled about it and often renewed the search. He finally got a gunsmith, named Harry Strouss, to make a new one. As it was of a different grade of workmanship than the rest of the gun, Father was dissatisfied with it. Some years afterward he got the boys together to make another search. He had the ground raked for some distance around the spot, and the leaves burned. After a long hunt he was as joyful as was the father of the prodigal son. Old Grey is to be carefully preserved by my descendants as an heirloom in memory of their ancestor who was a mighty hunter.

Post Script

After the recovery of the lost gun cock, Father took off the new one and replaced it with the old one, which is on it now. Of course the gun was at first a flint lock, as the percussion caps had not then been invented. This appears by an examination of the present lock. The bullet moulds that are not with the gun are the original ones that Father got from Allison.

– Roe Reisinger, April 21, 1901